The Mind of the South

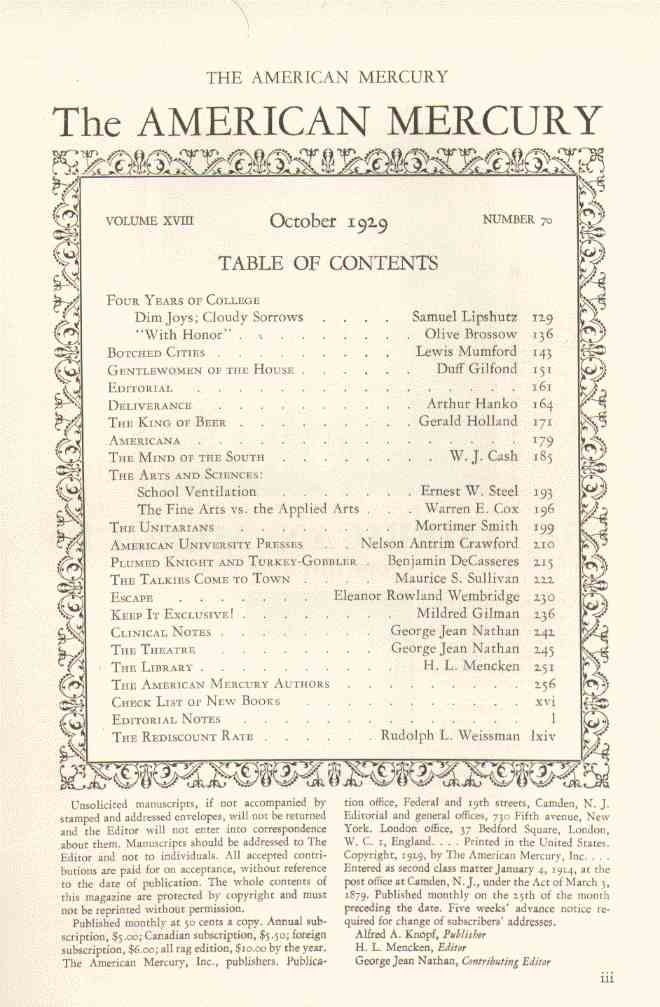

The Table of Contents of the original October, 1929 American Mercury, containing the article entitled, "The Mind of the South"

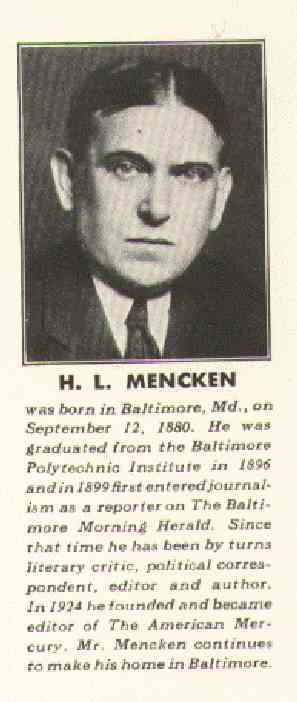

Mercury founder and editor H.L. Mencken, from an advertisement in the October, 1932 issue

Site Publisher's Note: "The Mind of the South", published in October, 1929, was the second Mercury article by Cash. It was this article which caught the eye of Mercury publishers Alfred and Blanche Knopf and led to an informal arrangement whereby Cash would write a book-length version of the ideas propounded in the article. Originally scheduled for release sometime in the mid-1930's, Cash would frustrate the Knopfs for several years as he agonized with perfection and missed deadline after deadline. While this timeline suggests that the book took over a decade to complete, in fact, the actual writing of the final version of the manuscript spanned only a few years in the late Thirties, after Cash had begun and in order destroyed several unsatisfactory attempts at the manuscript. The formal research for the book, and pretermitted attempts at its writing, however, did span approximately 12 years, beginning in earnest with the writing of the first articles for The Mercury; given the nature of the book, it is truer still perhaps to calculate the research time as the practical equivalent of Cash's lifetime.

(To see a somewhat humorous look back by Cash, from the vantage point of 1936, at the ample criticism he received, both from the press and his "fans", in the wake of publication of this article, go to "Criticism Of Criticism", The Charlotte News, July 5, 1936, at this site.)

The following note on the article, and the included footnotes in the body of the article, are by Professor Morrison from W.J. Cash: Southern Prophet:

In this Mencken-published article, bearing the same title as the book that was more than a decade away, Cash struck some of the major chords sounded in the later work. His thesis was to remain essentially the same: the continuity of the Old South mind with the New. One notices at once that Mencken’s smiling condescension is mirrored in Cash’s use in 1929 of such expressions as "the bogey of the Ethiop" and the "perpetual sweat about the nigger." There is not even a hint of such language in the later book.

(It should be noted that Morrison,

and other scholars, have suggested that Cash's early style was

borrowed heavily from and influenced by Mencken: in a letter from

Alfred Knopf to Morrison in 1965, however, Knopf, ultimately

publisher of the Morrison book, severely scolded Morrison for

this suggestion, saying that such a notion was absurd and that

"Cash's style was his and his alone". (Joseph L.

Morrison Papers, University of North Carolina Library at Chapel

Hill, North Carolina Collection.))

THE MIND OF THE SOUTH

ONE hears much in these days of the New South. The land of the storied rebel becomes industrialized; it casts up a new aristocracy of money-bags which in turn spawns a new noblesse; scoriac ferments spout and thunder toward an upheaval and overturn of all the old social, political, and intellectual values and an outgushing of divine fire in the arts—these are the things one hears about. There is a new South, to be sure. It is a chicken-pox of factories on the Watch-Us-Grow maps; it is a kaleidoscopic chromo of stacks and chimneys on the club-car window as the train rolls southward from Washington to New Orleans.

But I question that it is much more. For the mind of that heroic region, I opine, is still basically and essentially the mind of the Old South. It is a mind, that is to say, of the soil rather than of the mills—a mind, indeed, which, as yet, is almost wholly unadjusted to the new industry.

Its salient characteristic is a magnificent incapacity for the real, a Brobdingnagian talent for the fantastic. The very legend of the Old South, for example, is warp and woof of the Southern mind. The "plantation" which prevailed outside the tidewater and delta regions was actually no more than a farm; its owner was, properly, neither a planter nor an aristocrat, but a backwoods farmer; yet the pretension to aristocracy was universal. Every farmhouse became a Big House, every farm a baronial estate, every master of scant red acres and a few mangy blacks a feudal lord. The haughty pride of these one-gallus squires of the uplands was scarcely matched by that of the F. F. V’s of the estuary of the James. Their pride and their legend, handed down to their descendants, are today the basis of all social life in the South.

Such romancing was a natural outgrowth of the old Southern life. Harsh contact with toil was almost wholly lacking, as well for the poor whites as for the grand dukes. The growing of cotton involves only two or three months of labor a year, so even the slaves spent most of their lives on their backsides, as their progeny do to this day. The paternal care accorded the blacks and the white trash insured them against want. Leisure conspired with the languorous climate to the spinning of dreams. Unpleasant realities were singularly rare, and those which existed, as, for example, slavery, lent themselves to pleasant glorification. Thus fact gave way to amiable fiction.

It is not without a certain aptness, then, that the Southerner’s chosen drink is called moonshine. Everywhere he turns away from reality to a gaudy world of his own making. He declines to conceive of himself as the mad king’s "poor, bare, forked animal"; in his own eyes, he is eternally a noble and heroic fellow. He has always displayed a passion for going to war. He pants after Causes and ravening monsters— witness his perpetual sweat about the rigger. (No matter whether the black boy is or is not a menace, he serves admirably as a dragon for the Southerner to belabor with all the showiness of a paladin out of a novel by Dr. Thomas Dixon.l The lyncher, in his own sight, is a Roland or an Oliver, magnificently hurling down the glove in behalf of embattled Chastity.

Even Rotary flourishes primarily as a

1

Thomas Dixon, a native of Shelby, N.C.,

was a fiery orator committed to the cause of White Supremacy. His

first novel, the racist The Leopard’s Spots (1902), was a

financial success, so he retired from the Baptist ministry.

Drawing on material from his first three novels, Dixon then wrote

the photoplay which became, under the direction of David Wark

Griffith, the famous motion picture The Birth of a Nation ( 1915)

.

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 186

Cause, as another opportunity for the Southerner to puff and prance and be a noble hotspur. His political heroes are, typically, florid magnificoes, with great manes and clownish ways—the Bleases and the Heflins. (It is said sometimes, I know, that they are exalted only by the rascals and the dolts, but, on a basis of observation, I make bold to believe that, while all decent Southerners vote against them, most do so with secret regret and only for the same reason that they condemn lynching, to wit: that they are self-conscious before the frown of the world, that they are patriots to the South. )

When the Southerner has read at all, he has read only Scott or Dumas or Dickens. His own books have been completely divorced from the real. He bawls loudly for Law Enforcement in the teeth of his own ingenious flouting of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. He boasts of the purity of his Anglo-Saxon blood—and, sub rosa, winks at miscegenation. Yet, he is never—consciously, at least—a hypocrite. He is a Tartarin, not a Tartuffe. Whatever pleases him he counts as real. Whatever does not please him he holds as non-existent.

II

How this characteristic reacts with industrialism is strikingly shown by the case of the cotton-mill strikes in the Carolinas. Of the dozen-odd strikes which flared up a few months ago, not one now remains. All failed. New ones, to be sure, are springing up as a result of the unionization campaign which Thomas F. McMahon, president of the United Textile Workers of America, is waging in the region. But the U. T. W. A. failed in similar campaigns in 1920 and in 1923 and, in the light of recent history, I see no reason to believe that the present drive is likely to be any more successful.

Yet the peons of the mills unquestionably have genuine grievances, in the absolute. Wages rarely top $20. The average is from $11 to $14, with the minimum as low as $6. The ten-hour or eleven-hour day reigns. It is true that, as most of the mills own their own villages, houses are furnished the workers at nominal rentals. But, save in the cases of Cramerton, N. C., the Cone villages at Greensboro, and a few other such model communities, the houses afforded are hardly more than pig-sties. The squalid, the ugly, and the drab are the hallmarks of the Southern mill town. Emaciated men and women and stunted children are everywhere in evidence.

But the Southerner sees and understands nothing of this. Force his attention to the facts and he will, to be sure, appear for the nonce to take cognizance of them, will even be troubled, for he is not inhumane. But seek to remind him tomorrow of the things you have shown him today and you will discover no evidence that he recalls them at all; his talk will be entirely of the Cone villages and Cramerton and he will assume in all discussions of the merits of the case that these model kraals are typical of the estate of the mill-billy. The whole cast of his mind inhibits retention and contemplation of the hard facts, and he honestly believes that Cramerton is typical, that the top wage is the average wage. That is to say, he can honestly see only the pleasant thing. That is why, quite apart from antinomian considerations, the Southern newspapers almost unanimously denounced the accurate stories of the strikes printed by the New York World and the Baltimore Sun as baseless fabrications, inspired purely by sectional malice.

North Carolina furnished an interesting case study in this

phase of the Southern mind when, at Gastonia, thugs, combed from

the ruffians of two States and made sheriff’s deputies, were

loosed on a parade of inoffensive strikers, and dotards and women

were mercilessly clubbed. A rumbling of protest shook the State.

The Greensboro Daily News and the Raleigh News and

Observer went so far as to denounce the business editorially.

Whereupon—but that was all. Confronted by the damned facts,

North Carolina gaped for a moment,

THE MIND OF THE SOUTH 187

then hastily brushed the offensive object into the ashcan, poured itself an extra-long drink, and went back to the pleasant business of golf-gab or mule-swapping.

If I have made incidental mention of violence, let it not be inferred that, in general, the strikes have been crushed by the blackjack. It is a significant fact that only at mills owned and operated by Yankees, or, in the case of Elizabethton, Tenn., by Germans, has violence been in evidence. The native baron simply closes his mill and sits back to wait for nature to take its course. He understands, that is, that the strikes may be trusted to go to pieces in the mind of the striker himself.

That mind is, in every essential respect, merely the ancient mind of the South. It is distinctly of the soil. For the peon, in origin, is usually a mountain-peasant, a hill-billy of the valleys and coves of the Appalachian ridge. He is leisured, lazy, shiftless. He is moony, sharing the common Southern passion for the lush and the baroque. He yammers his head off for Heflin and Blease, not because they promise him better working and living conditions—they don’t—but because Heflin is his captain in the War Against the Pope, because Blease led him in that grand gesture for Human Freedom, that Storming of the Bastille—the flinging open of the gates of the South Carolina penitentiary. He crowds such swashbuckling and witless brotherhoods as the Klan, the Junior Order, the Patriotic Order Sons of America, and the American Legion. He is passionately interested in the shouting of souls "coming through" at a tent-revival, in the thrilling of his spine to "Washed in the Blood" at the Baptist synagogue, in a passing medicine show, and in the next installment of "Tiger Love" at the Little Gem. But in such hypothetical propositions as his need of a bathtub, in such prosaic problems as his economic status, he is interested but vaguely if at all.

In brief, he is totally blind to the realities of his condition. Though for a quarter of a century he has been in contact with industry, and has daily rubbed elbows with a standard of living higher than his own, his standards remain precisely those of a hill-billy. He holds it to be against God to take a bath at any other time than Saturday night. Often enough, indeed, he sews himself into his underwear at Hallowe’en, not to emerge again until the robin wings the northern way. Scorning the efforts of Y. M. C. A. secretaries to lure him into shower-baths, he continues, with a fine loyalty to tradition, to perform his ablutions in the tin tub which does duty on Monday as the family laundry.

So with everything. He is not displeased with his millshanty—for the reason that it is, at its worst, a far better house than the cabins of his original mountain home. And he has little real understanding that his wages are meagre. In his native hill society, money was an almost unknown commodity and the possession of ten dollars stamped a man as hog-rich; hence, privately and in the sub-conscious depths of him, he is inclined to regard a wage of that much a week as affluence. He is still at heart a mountain lout, lolling among his hounds or puttering about a moonshine-still while his women hoe the corn. He has no genuine conviction of wrong. His grievances exist only in the absolute. There is not one among them for which he is really willing to fight. And that is the prime reason why all Southern strikes fail.

III

Moreover, the mind of the Southerner is an intensely

individualistic mind. There again, it strikes back to the Old

South, to the soil. The South is the historic champion of States’

Rights. It holds Locke’s "indefeasibility of private

rights" as axiomatic. Its economic philosophy is that of

Adam Smith, recognizing no limitations on the pursuit of self-interest

by the individual, and counting unbridled private enterprise as

not only the natural order but also the source of all public good.

Laissez-faire is its watchword.

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 188

The Southerner is without inkling of the fact that, admirably adapted as such a philosophy was to the simple, agricultural society of the Jeffersonian era, it is inadequate for dealing with the industrial problems of today. He has never heard of the doctrine of the social function of industry and would not understand it if he had. He cannot see that industrialism inevitably consolidates power into the hands of a steadily decreasing few, and enables them, if unchecked, to grab the lion’s share of the product of other men’s labor; he cannot see that the worker in a machine age is not an individual at all but an atom among atoms—that he is no longer, and cannot possibly be, a free agent. Under the Southern view, even a cotton-mill is an individual. If a peon cares to work for the wage it chooses to pay, very well; if he doesn’t, let him exercise a freeman’s privilege and quit. But for him to combine with his fellows and seek to tie up the operation of the mill until his wages are raised—that, as the South sees it, is exactly as if a lone farm-hand, displeased with his pay, took post with a shotgun to bar his employer from tilling his fields.

The lint-head of the mills, indeed, is the best individualist of them all, and for this there is excellent reason. Often enough he owns a farm, his ancestral portion in the hills— rocks, pinebrush, and abrupt slopes, but still a farm, well adapted to moonshining. If he is landless, there are hundreds of proprietors eager to secure him as a tenant, an estate in which he will not have to work more than three months out of twelve. As a result, there is a constant flow back and forth between the soil and the mills. Thus the Southern peon is not, in fact, and as an individual, as irrevocably bound to the wheel of industry as his Northern brother, since he may always escape to churldom. The equally valid fact that, because only a handful can escape at any given time, the mass of his fellows are held irretrievably in bondage is lost upon him. He is always, in his own eyes, a man apart. He exhibits the grasping jealousy for petty personal advantage, the refusal to yield one jot or tittle for the common good, characteristic of the peasant. If, by a miracle, he is ambitious, his aspirations run, not to improving his own status by improving that of the class to which, in reality, he is bound, but to gaudy visions of himself as a member of the master class, as superintendent or even president of the mills. His fellows may be damned.

Another excellent reason, then, for the failure of Southern strikes is the impossibility of holding in organization the individualized yokel mind. The peon, to be sure, will join the union, but that is only because he is a romantic loon. He will join anything, be it a passing circus, a lynching-bee, or the Church of Latter Day Saints. He will even join the Bolsheviks (as at Gastonia, where the strikers were organized by the National Textile Workers’ Union), though he is congenitally incapable of comprehending the basic notion of communism. The labor-organizers, with their sniffling pictures of his dismal estate, furnish him with a Cause for which he can strut and pose and, generally, be a magnificent galoot. And the prospect of striking invokes visions of Hell popping, the militia, parades, fist- fights and boozy harangues—just such a Roman holiday as he dotes on. By all means, he’ll join the union!

But when flour runs low in the barrel, when monotonous waiting

succeeds the opening Ku Klux festivities, when fresh clodhoppers,

lured by the delights of moviehouses and icecream joints, begin

to pour in and seize the vacant jobs in the mills, and when a

strike-breaker drops around to the back door to say that, while

the boss is goddam sore, he is willing to give everybody just one

more chance, well, the lint-head, who has no deep-seated sense of

wrong, who all along has rather suspected that the business he is

embarked on is indistinguishable from road-agentry, and who

decidedly likes the ego-warming backslap of the boss, does the

natural thing for a romantic and sidesteps reality—does the

natural thing for an individualist and goes back to work.

THE MIND OF THE SOUTH 189

IV

Finally, the mind of the South begins and ends with God, John Calvin’s God—the anthropomorphic Jehovah of the Old Testament. It is the a priori mind which reigned everywhere before the advent of Darwin and Wallace. The earth is God’s stage. Life is God’s drama, with every man cast for his role by the Omnipotent Hand. All exists for a Purpose—that set forth in the Shorter Catechism. The Southerner, without, of course, having looked within the damned pages of Voltaire, is an ardent disciple of the Preceptor Pangloss: "It is demonstrable . . . that things cannot be otherwise than they are; for all being created for an end, all is necessary for the best end. Observe that the nose has been formed to bear spectacles—thus we have spectacles." Whatever exists is ordered. Even Satan, who is forever thrusting a spoke into the rhythm of things, is, in reality, ordained for the Purpose. But that in nowise relieves those who accept his counsels or serve his ends; their damnation is also necessary to the greater glory of God.

Under this view of things, it plainly becomes blasphemy for the mill-billy to complain. Did God desire him to live in a house with plumbing, did He wish him to have better wages, it is quite clear that He would have arranged it. With that doctrine, the peon is in thorough accord. He literally holds it to be a violation of God’s Plan for him to have a bath save on Saturday night. Could he have a clear-seeing conviction of his wrongs, could he strip himself of his petty individualism, he would, nevertheless, I believe, hesitate under the sorrowing eyes of his pastor, wilt, and, borne up by the promised joys of the poor and torments of the rich in the Life to Come, go humbly back to his post in the mills. If you doubt it, consider the authentic case of the mill-billy parents who refused to let a North Carolina surgeon remove cataracts from the eyes of their blind daughter on the ground that if God had wanted her to see He would have given her good eyes at birth. The peon is always a Christian.

The South does not maintain, of course, that, even in a closed, ordered world, change is impossible, but such change must always proceed from God. In the case of the lint-head, for example, it could come about in two ways. God could directly instruct the barons, who are such consecrated men that they pay the salaries not only of their uptown pastors but of the peon’s shepherds as well, to give the peon better wages and a bathtub, in which case He, of course, would be promptly obeyed. It is clear that He has not yet resorted to this method, which, indeed, must be described as somewhat extraordinary. The more usual way would be for Him to communicate His wishes to His immediate servants, the holy men. These holy men hold audience with Him several times daily, so that the South is in constant touch with His plans. At this writing, the uptown pastors seem agreed that God is insistent that there must be less raging after vain things like porcelain baths and more concern with the Higher Life. With this report that of the peon’s shepherds coincides perfectly.

The liaison thus maintained between God and the South through

His intelligence men is the explanation of many things—for

instance, the paradox that our States’ Rights,

individualistic, laissez-faire hero is the chief champion

of Prohibition. Many explanations for that have been offered, but

it seems to me to be pretty evident that the Noble Experiment

arose in the South primarily from the fact that the college of

canons went into a huddle with God and emerged with the news that

He wanted a Law. The gallant Confederate, of course, was and is

not, in fact, dry. But if God wanted a Law—well, He got it.

That is why the South will tolerate no monkey- business with the

Volstead Act. It is God’s Law. And therein, indeed, is

stated the South’s whole attitude toward morals. Adultery,

thievery, horse-racing, cock-

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 190

fighting, whatnot, are wrong not because they react unfavorably on human society but because they are forbidden by God, either in the Bible or in the dictums of the chosen vessels of His Will. Individual transgressions of most of these laws may, to be sure, be glossed over by an extra dollar on the collection plate on Sunday, but to oppose the laws themselves is to oppose God. Blasphemy is the first crime in the Southern calendar.

It follows, from both his romanticism and his theology, that the Southerner is ungiven to reflection. Thinking involves unpleasant realities, unsavory conclusions; and, happily, there is no need for it, since, as everything is arranged by God, there is nothing to think about. The South, with more leisure than New England, has yet produced no Emerson nor even a Thoreau. Though the British friars shrieked and tore their garments as lustily when Darwin advanced the doctrine of evolution in 1859 as did their Southern brethren when such Catalines as Dr. W. L. Poteat, of North Carolina, bore it below the Potomac forty years afterward, yet all England accepted it within two decades, while the South, in significant contrast, is no more reconciled to it today than in 1900. All that matter of the origin of man was settled very long ago—set down in Genesis by God Himself. To question it is to blaspheme. All ideas not approved by the Bible and the shamans are both despised and ignored. And, indeed, a thinker in the South is regarded quite logically as an enemy of the people, who, for the common weal, ought to be put down summarily—for, to think at all, it is necessary to repudiate the whole Southern scheme of things, to go outside God’s ordered drama and contrive with Satan for the overthrow of Heaven.

All problems are settled categorically. Maxim and rule are enough. Precedent is inviolable. And nice distinctions are, of course, impossible. A rigger, for example, is either a vile clown or an amiable Uncle Tom. If he insists on upsetting things by being something else, he passes, like Elijah, in a chariot of fire, and is wafted to his reward on wings of kerosene (The Southerner, faced with any reality which refuses to fit into his rose-colored, pigeonholed world, quietly abolishes it. Lynching is not only a romantic gesture but a protective one as well. ) The more serious and intelligent of the cotton-mill operatives, unlike their peers in most industrial hives, are never found pondering Prince Kropotkin, Karl Marx, or even Upton Sinclair. Their minds run rather to the problem of convincing sinful souls of the merits of total immersion. Their own case is disposed of by maxims: "The poor we have with us always," "Servants, obey your

masters" and "God’s in His Heaven; all’s right with the world."

It is this lack of thoughtfulness which accounts for the fact that the mind of the South is almost impervious to change, that, for a quarter of a century, it has successfully resisted the steadily increasing pressure of industrialism, blithely adopting the Kiwanis moonshine—all those frothy things it found compatible—but continuing, in the main, to move through the old rhythms. I have paid much attention herein to the cotton-mill peon because it seems obvious to me that if change is to come about in the Southern mind, it must arise from him, for he is in most direct contact with industry and it is in his status that the inadequacy of the old formulae is most clearly evident. Everywhere revision of values and adjustment of the agricultural mind to industrialism have been brought about by the revolts of the laboring classes, since it is the natural tendency of the upper classes to assume that quand le Roi avait bu, la Pologne etait ivre, and to ask: "When all goes so well, why trouble to change?"

But the Southern peon is scarcely touched by industrialism. He

accepts; he does not question and challenge. His desultory

revolts have not arisen from his own convictions but from the

urging of professional agitators. Even the recent spontaneous

walkouts in South Carolina were inspired,

THE MIND OF THE SOUTH 191

not by protest against wages and living conditions, but by collision between the peon’s native shiftlessness and so-called efficiency system introduced in Yankee-owned mills; they prove nothing save that he declines to become industrialized.

V

But if the much-proclaimed industrialization of the South is merely a matter of externals, the remaining ingredients of the New South formula are scarcely more than wind. The money-bags do exist, certainly—a handful of parvenus. But they have begotten no new cultural noblesse, nor are they likely to. Sworn enemies of the arts, of all ideas dating after 1400, and of common decency, they have imported the senseless Yankee dogma of work for work’s sake, and seek rather to destroy than to increase that leisure which must be the basis of any culture. All their contributions to educational institutions, of which the Duke gift2 is the outstanding example, have been motivated by a desire to perpetuate the old order, not to create an enlightened new one. As for the prognostications of social, political, and intellectual revolution, the prophecies of the outpouring of heavenly fire—they, like the great Woof-Woof in Kansas,3 arise from nowhere; like the earth, they are hung upon nothing—unless, indeed, it be the cabalistic imaginations of those occult professors who write books called "The New South" or "The Rising South" or "The Advancing South."

There, to be sure, is the breaking of the Solid South, the swinging of traditionally Democratic States into the Republican column last Fall. But that was proof, not that the mind of the South had changed, but that it was unchanged. Satan had seized the Democratic party, and the oriflamme of God, as was witnessed by all the holy men, had passed to the keeping of the Republicans. The Southerner merely chose to remain loyal to the All Highest. The sadly moth-eaten Cause of White Supremacy was laid aside for two shiny and extraordinarily juicy new ones—the plot of the Pope ( Satan’s cousin) and the scarcely less electric plot of the Rum Ring. Save among cotton-mill barons and a few Babbitts, the Hoover elan and Republican principles—whatever, and if, they may be—had nothing to do with the matter. As I write, the De Priest incident seems to have miraculously refurbished and revivified the bogey of the Ethiop—and the Southern Democratic bosses are engaged in identifying themselves with the War on the Pope by bellowing for Raskob’s scalp and openly threatening to repudiate the national party if Great Moral Ideas are again defied. Whichever party best combines causes and monsters and clinches its claim to the banner of God will win. Party labels may or may not be changed. In any case, I believe, the mind of the South will remain the same.

There are, too, of course, Mr. James Branch Cabell, Mr. DuBose

Heyward, Mrs. Julia Peterkin—a little group of capable

craftsmen who have abandoned the pistols and coffee-lilacs and

roses-sweetness and light formulae of Southern litterateurs to

cope with reality. It is true also that the South swells with

pride in them. But—I have myself watched a lone copy of

"The Cream of the Jest" gather flyspecks for two years

in a bookshop not two hundred miles south of Monument Avenue. For,

gloss it over as one will, it is undeniably true that Mr. Cabell’s

persons do things forbidden by the Bible, that Poictesme, as

compared with the satrapies of Bishops Cannon, Mouzon,4 et al., is in sin, and that (O

base infidelity! ) he fails to view these matters with becoming

indignation. Of late days, I have heard often the complaint that

"Mamba’s Daughters" is both pointless and untrue

to the Southern Negro, which last is to say that Mr. Heyward’s

portrayals fit neither the Uncle Tom formula nor that of the

vaudeville buffoon. And Mrs. Peterkin’s "Scarlet Sister

Mary" is barred from the library at Gaffney, in her native

State of South Carolina, as an immoral book. The gloomy fact is

that, however much

2 The Duke gift was that of James Buchanan Duke, the tobacco and utilities magnate who, in 1924, handsomely endowed Trinity College (Methodist) on condition that the institution change its name to Duke University. Mr. Duke shrewdly saw to it that the Duke Endowment was bankrolled by stock in the Duke Power Company so that the prosperity of the one was tied to the other. Thus, "adverse" state taxation upon the Duke Power Company could be, and in fact was, avoided by appealing to legislative sentiment against "harming" the beneficent Duke Endowment.

3 This reference probably is to William Allen White, the Sage of Emporia, and to his attempts to discredit .Al Smith, whom Cash had championed, during the presidential campaign of 1928.

4 James Cannon Jr. and Edwin D. Mouzon were

Southern Methodist bishops who were prominent, as was William

Allen White, in the fight to retain national prohibition, Cannon

attaining unprecedented influence through his political

infighting against Al Smith in 1928. Later, when Cannon was shown

to have been gambling in the stock market, Mouzon became perhaps

his chief adversary within the church.

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 192

patriotic pride the Southerner may take in the fame of these people, he is bewildered and infuriated by their works.

Lastly, there are such diverse factors—to mention a few out of many—as Odum’s Social Forces and Koch’s Playmakers at the University of North Carolina, Poteat’s teaching of evolution in face of the stake to young Baptists at Wake Forest College for the past thirty years, and the Commission for Inter-racial Cooperation, which aims to foster a more reasonable attitude toward the Negro. It would be foolish to say that they have had no civilizing influence. But it is insanity to claim that they have had any definite effect on the mass of Southerners, to assert that there is any prospect of their engendering, at an early date, a revolution of thought in the South. The men who are responsible for these things, like the artists I have discussed, are not, in any true sense, of the Southern mind. All of them are of that level of intelligence which is above and outside any group mind. They are isolated phenomena, thrown up, not because of conditions in the South, but in spite of them.

Eventually, of course, must come change. Perhaps, indeed, the

beginning of it is already at hand. For, undeniably, there is a

stir, a rustling upon the land, a vague, formless, intangible

thing which may or may not be the adumbration of coming upheaval.

Tomorrow—the day after—eventually— the cotton-mill

peon will acquire the labor outlook and explosion will follow. In

the long run the mind of the South will be remade. Will that

bring on the millennium which the prophets profess to see as

already in the offing? Will Atlanta become another Periclean

Athens, Richmond a new Augustan Rome? I don’t know,

certainly, but I glance at the cotton-mill barons, the only

product of readjustment yet in evidence, and take the liberty of

doubting it. I suspect that the South will merely repeat the

dismal history of Yankeedom, that we shall have the hog

apotheosized—and nothing else. I suspect that we shall

merely exchange the Confederate for that dreadful fellow, the go-getter,

Colonel Carter for Mr. Lowell Schmaltz, the Hon. John LaFarge

Beauregard for George F. Babbitt. I suspect, in other words, that

the last case will be infinitely worse than the first.

Go Home -- Go to 3rd article: "The War in the South"